What's Sustainability in Arabic?

May 2002

The further we can see back into history, Churchill argued, the further we can see into the future. John and Elaine Elkington have just returned from Syria, where the roots of civilization can be traced back beyond 7000 BC – and where they began to see the world (and the sustainability agenda) through Arab eyes.

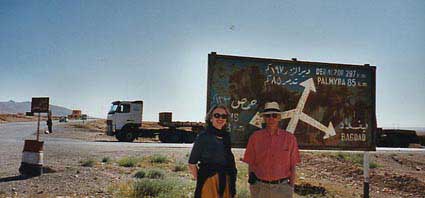

Not taken: the road to Baghdad

John writes:

I have travelled continuously in 2002, SustainAbility’s fifteenth anniversary

year, to places as various as Canada, Hong Kong and Nigeria. But nothing compares

with the trip Elaine and I have just made to Syria.

As SustainAbility Core Team members know, this was both a 2-week holiday and an effort to take some of the 3-month sabbatical SustainAbility offered me in 1999, when I hit 50. The trip provided a rare opportunity to pull back and look at elements of the bigger picture.

And at a time when the news media are full of stories of suicide bombings in Israel and the assassination of far Right politician Pim Fortuyn (who wrote a book called Against the Islamicisation of Our Culture) in The Netherlands, we often found ourselves thinking about the high-energy collisions between the worlds of Islam and of secular modernism.

Why Syria?

Many asked us this question. The reason Elaine booked the Syrian trip was simple: I had long wanted to see what is considered to be the pre-eminent example of Crusader castle building, Krak des Chevaliers. And Krak (see photograph) just happens to be in Syria.

Elaine had come across ACE Study Tours though Amanda Spencer-Cooke (mother of Andrea, ex-Core Team member). Based in Cambridge, UK, ACE is a non-profit organisation that invests a proportion of its profits back into archaeological and community projects in the countries its tours visit.

ACE Study Tours www.study-tours.org

We had hoped to go last October, but I was already booked to speak at a conference – and then came September 11 and its aftermath. Not surprisingly, eyebrows were raised when we decided to go this April, indeed many other tours to the region had been cancelled. But despite a few last minute cancellations of bookings, our tour went ahead.

We thought hard before going. Syria’s turbulent history and reputation as an international troublemaker would give anyone pause. The one American couple on the tour had been given a real pummelling by friends and family in the US. One of their daughters and her husband ended up not talking to them.

Krak des Chevaliers: becalmed medieval ‘battleship’

Given the events in Israel, we were looking for Foreign Office advice on whether to travel right up to the last day. And knowing that we would be visiting Hezbollah territory in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, to see the temple complex at Baalbek, Elaine was convinced we would end up as hostages held for several years in a broom cupboard, like Terry Waite and others.

How does this relate to SustainAbility?

Links there are. For one thing, after 11 September, I was keen that SustainAbility should open up a wider window onto the Arab world. As I hope to show, the trip began that process. But – in our anniversary year - it has also helped me look back at what we do from a very different perspective and take stock.

Dead but not forgotten: President Assad and

heir Bassel, killed in car crash, 1994

Or at least that’s the grown up version. The fact is that the real impetus for the visit goes back to the years I spent as a child in Cyprus in the late 1950s. Following visits to the ruins of Richard I’s extraordinary castle, St Hilarion, I became fascinated by the Crusading era.

As a child, Richard the Lionheart (Coeur de Lion) was a hero of mine. Much of my current interest in corporate brands stems directly from my early interest in heraldry and chivalry. But the more I read about the Crusades, the more nuanced my views became.

One book I read in the early 1960s was the novel Knight Crusader, by Ronald Welch. A year or two back, Elaine tracked down a copy of the book, long out of print, and I was again struck by how sympathetic it was to Saladin and to the Arab point of view.

This perspective was reinforced just before we left for Syria by one of two books SustainAbility Council member Jim Salzman sent me: The Crusades through Arab Eyes, by Amin Maalouf. The book ends up with a short, insightful Epilogue on which I shall draw in a moment.

The Crusaders – like SustainAbility – were on a mission. These days, sociologists talk of the "social construction of reality". Simply put, we all live in reality bubbles, as the Crusaders did. Whether ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ in its analysis, the sustainability agenda is just one more reality bubble. If we want to appeal to a wider world, the ability to see the world through different eyes – and to work across very different reality bubbles - will be a key skill.

Sure-footed reality bubble: shepherd and flock, Baalbek

My evolving understanding of the Crusades was one way in which I began to break out of the reality bubble I grew up in. As a teenager, for example, it had come as a shock to find that Saladin, or Salah al-Din Yusuf, was considerably more civilised than most of the Crusaders who had invaded the ‘Holy Land’.

Why are we still talking about the Crusades?

Extraordinary, isn’t it? The Crusades in the ‘Holy Land’ lasted less than 200 years, from 1096 to 1291, when the last Crusaders were swept into the sea. (Indeed, some Arabs see Israel as a latter-day crusading state, arguing that it will also eventually be swept into the sea.) But the shock-waves caused by the Crusades still reverberate in our world.

The Pope may have apologised recently for the crimes against humanity committed by the Crusaders, including the ferocious massacre of many, many thousands of men, women and children when the First Crusade stormed Jerusalem, but it is hard not to see the successive Crusades through Arab eyes - as so many barbarian hordes.

The Arab world is still outraged by what was done in those years, even if they, too, committed outrages when they later stormed across Asia Minor and into Europe, taking Constantinople in 1453 and reaching the gates of Vienna in 1529.

Memories of the Crusades are still raw in some Arab minds. Mehmet Ali Agca, the Turkish extremist who shot the Pope in May 1981, wrote a note explaining that he had "decided to kill John Paul II, supreme commander of the Crusades". President George W. Bush also triggered Arab outrage when he labelled the campaign against al-Qaeda a ‘crusade’.

And in the wake of September 11 some people who knew their history drew parallels between Osama bin Laden and Rashid al-Din Sinaan, head of ‘The Assassins’ and known to the Crusaders as ‘The Old Man of the Mountains’. Just as bin Laden got young men to commit suicide by flying hijacked planes into buildings, so Sinaan got young men to undertake assassination attempts from which they could not hope to return - some say by feeding them hashish, to give them a taste of the pleasures they would experience in the afterlife.

MIG and mosque: Damascene mix’n’match

What did you see?

Syria bills itself as the ‘Land of Civilizations’. Truly, this area has been a crucible in which different peoples and different cultures have collided, allied and alloyed. As we walked among the children in outlying villages, we were struck by the different hair colours, including a fair number of blonde and red heads. Some of that may go back to Crusader genes, but some may be more recent, for example linking to the French Mandate period early in the 20th century.

We visited a wide variety of sites, as they came up on our itinerary, but here is an attempt at a rough chronological ordering of some of our favourites:

— Ugarit, hard by the coast north of present day Latakia. First occupied around 7000 BC, rising to prominence around 3000 BC when it traded copper with Cyprus and Mesopotomia, then destroyed in 1180 BC by the ‘Sea Peoples’ (identity unknown, but possibly the ancestors of the Palestinians). The harbour is long since silted up, the site covered in wildflowers. We went underground into beautifully shaped tombs. And as someone who has made much of his living by writing, I was fascinated by the claim that Ugarit developed the first – or one of the first – alphabets, between 1400 and 1300 BC. The descendants of the people of Ugarit included the Phoenicians, whose 50-odd colonies spread the alphabet around the Mediterranean. (I am currently reading a book on the ‘Gutenberg Revolution’ One interesting question – why didn’t the Chinese, Japanese and Koreans, who had the main elements of movable type printing 2,000 years ago, beat Gutenberg to the post? One answer: they may have had ways of writing down their ideas in pictograms, but they lacked an alphabet – which makes movable type printing possible.)

In the footprints of the gods, ‘Ain Dara temple

— ‘Ain Dara, in the Afrin valley, near the Turkish border. This was the first ‘tell’ we had climbed, a man-made mountain largely created by successive layers of human settlement, with each settlement built on the rubble of earlier ones. The most interesting period of settlement here was neo-Hittite, dating back to the beginning of the first millennium BC, after the Sea People’s invasion. Atop the tell was an extraordinary temple, surrounded by the remains of giant winged lions carved out of black basalt. The threshold to the temple was formed from two huge stones, the first of which had a giant footprint in it, the second two. These may have represented the footprints of the gods. From the nearby Afrin river came the constant croak of frogs. We encountered one bright green frog in the temple: beautiful, watchful, silent. And lots of iguana-like lizards.

— Apamea, on the east side of the Orontes Plain, a fertile valley between mountains. Much of the land, which was once used to raise horses was reclaimed from swamps. Originally settled by the Seleucids, who followed Alexander the Great into the region and flourished between 333 and 64 BC, displacing the Achaemenid Persians and the forces of Egypt’s Ptolemies as occupiers of much of what is now Syria. The Romans took over in 64 BC, also using the city as a forward military post and to breed horses for the army. The city was surrounded by 6.3 km of walls and you can still see extraordinary vistas of Roman columns marching across the grasslands, particularly the colonnaded main street built during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Later came earthquakes, the Persians (who razed the city), the Byzantines and Arabs. Waves of poppies stream in the wind. Once again, walking among the glorious ruins, you recall Shelley: "Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair …"

Look on my works … fragment of Roman colonnade, Apamea

— Dura Europos, one of the most wonderful sites we visited, high above the Euphrates, was founded after the death of Alexander as part of a network of Seleucid military colonies. Later it came under the control of the Parthians, then of the Romans. After the first wall paintings were found here, by accident by British soldiers digging trenches in 1920, an extraordinary range of early Judaic and Christian art was dug up – with the result that Dura Europos has been described as "the Pompeii of the Syrian Desert". A polyglot city, this had an amazing diversity of temples, to every conceivable god. Despite the frantic attempts of the Romans to buttress the long walls, at least one tower was undermined by the Persians – indeed, the skeleton of one of the sappers was found in the tunnel, with freshly minted coins in his pocket dating the siege to 256 AD. As we walked up onto the huge citadel, overlooking the Euphrates, a spray of hawks and what may have been bee-eaters fanned out from beneath my feet, soaring out over the river far below.

— Baalbek, in the Lebanon, Hizbollah (Shi’ite, ‘Party of God’, Iranian-backed) territory, and the site of a massive temple complex built over some 200 years, by 10 generations of slaves. Originally a temple to Baal, the Romans turned this into a complex for a number of their gods, particularly Jupiter. The monumental size of the columns and other structures was astounding. In its heyday, animals were sacrificed here in huge numbers, with a vast stone gutter draining the blood away into a deep well. Across the road was a delightful old hotel, its walls lined with wonderful drawings by Jean Cocteau, who paid his bills with his art.

— Palmyra, way over on the east side of Syria, an oasis city, featuring a giant temple to Bel, a Semitic god who was eventually blended with Zeus (as Zeus-Belos). Often said to justify a visit to Syria on its own. First settled at the end of the third millennium BC, the area came under the control of first the Seleucids, then the Romans. Under the latter, the city became extremely wealthy, although its fate depended on the extent to which the Romans and Arab dynasties could control the desert tribes, protecting the caravan traffic. The wealth is shown in the sheer profusion of richly appointed tower tombs and underground tombs scattered throughout the area. We visited several, including one discovered when a truck which had stopped on a road suddenly disappeared into the ground. On the second evening, we went up to the nearby Arab castle, overlooking the oasis, and watched the sun set over a glass (or plastic beaker) of arak. The next day, after we had left, a major dust storm hit. We could see the haze as far away as Damascus.

Euphrates, from old citadel, Dura Europos

One extraordinary local: Queen Zenobia. Following the murder

of her husband, Odenathus in 267 AD, she took control of the powerful Palmyran

army and invaded both Palestine and Egypt, hoping to take over the eastern

end of the Roman Empire. Emperor Aurelian had other ideas: he counter-attacked,

razing Palmyra. Zenobia was captured and taken to Rome in golden chains, where

she was humiliated in a victory parade. She died at the hands of the Romans

and was recently featured in a 22-part TV series shown throughout the Arab

world, her struggle against the Romans seen as a metaphor for Syria’s

recent struggle against Israel.

In the midst of all this comfortably romantic historical violence, some of

us were reminded of current-day problems in Syria. Nearby Tadmor Prison is

notorious: it holds political prisoners of many persuasions. In 1980, following

the Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt on President Assad’s life, a special

unit is believed to have shot 1,000 prisoners dead in their cells. According

to the Rough Guide to Syria, cells of 5m by 20m hold up to 70 prisoners –

although the number rose to over 200 in the wake of the Muslim Brotherhood’s

1982 uprising.

— Bosra, 140km south of Damascus, a city built from black basalt and once known as Nova Trajana. After Palmyra, this is the most important Roman site in Syria. The surrounding country is now fairly harsh, but in Roman times it was greener - one of the Empire’s key granaries. The real highlight is the virtually intact Roman theatre, which survived because the Ayyubids built a castle around it and on top of it. So you walk through the gates of what seems like a standard Arab castle and emerge into the most extraordinary virtual reality generator. 6000 spectators could sit in the 37 tiers of seats, with room for another 2-3,000 standing. A conversation on the stage can be heard at any point around the 102m-wide theatre. It was a bit like Dr Who’s Tardis, but instead of walking into a police kiosk and finding a vast internal space, here you walked into a castle and discovered this time machine from the second century AD. The experience was made even more dramatic by the fact that this was May Day, so the place was full of young people, dancing in circles to clapping and drumming.

May Day: youngsters dancing in Roman theatre, Bosra

— Resafe, or Sergiopolis, a ruined city in the desert between Aleppo and Palmyra. Although mentioned in Assyrian texts and in the Bible, Resafe really took off when the Roman Emperor Diocletian built a frontier fortress here. The settlement took on new significance in Byzantine times, following the excruciating martyrdom of a Roman soldier, Sergius, during Diocletian’s persecution of Christians in 305 AD. Following his refusal to sacrifice to Jupiter, he was forced to walk from the Euphrates to the city in spiked shoes, and was then led by a rope through his tongue to his execution. The city’s walls were once faced with quartz so that it shone like a diamond in the desert. It was sacked by the Persians, with further damage done by the Abbasids, Baibars, at least one earthquake and the Mongols. Much of the walls still stand, but the internal area is pock-marked by holes made by treasure-hunters.

— The Dead Cities are found in limestone country between the Orontes and Afrin rivers. The first settlements appeared from the first century to 250 AD, with greater prosperity developing between 340 and 500 AD, and the saturation point reached in the mid-sixth century. Decline began when most parts of the later Roman or Byzantine Empire were disrupted – and the collision between Arab and Byzantine worlds led to much reduced trade in olive oil and other local products. Because of the shortage of trees locally, most of the buildings were largely built of stone (including ceilings, cupboards and stairs), which means that over 700 settlements survive in remarkably good shape.

— Saint Simeon’s Church, the most monumental Christian church built before the masterpieces of Northern Europe – and dedicated to the memory of a particularly turbulent saint (Simeon Stylites, from the Greek stylos for pillar), who wore spiked girdles that drew blood and buried himself up to the chin in the ground. Ended up living atop a column 12 to 18m high for some 38 years. He disliked women, even spurning his mother. A story is told of one who woman who came into his presence – and promptly dropped dead. Whatever, he died on 24 July 459 – and was the subject of an unholy race by 600 imperial troops, who took his body away to Antioch, from whence it was later taken to Constantinople. Even so, the site became the focus of a major monastic community and of pilgrimage from around the Byzantine Empire. Like today’s school gunmen, St Simeon spawned a wave of copycats.

The main reason I wanted to go to Syria, a trio of Crusading era castles, Krak des Chevaliers, Qalaat Sayhun (also known as Qalaat Saladin and, earlier, as Château Saône) and Masyaf.

— Krak, which I had wanted to visit since I was in my early teens, has been described as the supreme Crusader castle, to Crusader building what the Parthenon was to Greek temples and Chartres to Gothic cathedrals. Perched high on a hill called Jebel Kalakh, almost 1km above the surrounding plain, Krak was everything I had expected – and more. Elaine had been seriously ill the previous day, which meant that we missed the group visit. But the tour organisers, Assur, got us a car and guide and, as a result, we were able to visit on our own time. Our day there was one of the high points of my life. The sheer power of the structure beggars the imagination. Even so, the Mameluke Sultan Baibars managed to turf out the demoralised Knights Hospitaller in 1271 from what was then described as the "key to Christendom".

— Qalaat Saladin was mainly built by the Crusaders, but taken by Saladin. Lawrence of Arabia called it "the most sensational thing in castle-building I have seen". The morning mist was rolling up from the dramatic ridge on which the ruins stand, in the midst of precipitous ravines. In the distance you can see the Mediterranean. Everything here was built "big, solid and magnificent", with a key feature being the extraordinary 28m high rock monolith, which once supported a drawbridge. The monolith stands in a formidable 156m long ravine cut from the living rock, 28m deep and 14m to 20m wide, dating mainly from Byzantine times. We were taken around by a man born within the walls of the castle, when it was still possible for ordinary folk to live there. One feature he showed us: a secret spiral stairway that runs from the roof of the keep, down through the giant central pillar in floor after floor, and then through the living rock of the mountain to the river, far below. The idea, apparently, was to take besiegers from behind.

— Masyaf wasn’t a Crusader castle. It is probably the most famous of a network of Ismaeli (splinter group from the Shi’ites) castles, to which these people fled following Sunni persecution in Aleppo and Damascus. It is certainly the best preserved of the castles of the cult known as the ‘Assassins’. Although briefly seized by the Crusaders in 1103, they couldn’t hold it. Instead, it became a stronghold of Rashid al-Din Sinaan, ‘The Old Man of the Mountains’. The Assassins terrorised Crusaders and Saracens alike. Saladin tried to take the castle by siege in 1176, but suddenly gave up when a threatening verse, a dagger and a collection of hot cakes appeared on his pillow in his closely guarded tent. It took another century before the Assassins were subjugated by Baibars.

My one regret: we drove past Qalaat Marqab, on the Tartus/Latakia motorway, a predominantly black castle once described as a "triumph of the gigantic". When this mighty stronghold fell, in 1285, the way was open for the Crusaders’ enemies to roll them up and toss them into the sea.

Citadel and bathhouse, Aleppo

— Aleppo’s citadel, which has produced remains going back at least to neo-Hittite times, was probably first fortified in the Seleucid era (333-364 BC). In the fourth century AD, it was visited by the Roman Emperor, Julian the Apostate, who had overthrown the link between the Empire and Christianity and offered sacrifices to Zeus there. During the Crusading era, the citadel was developed into one of the most impregnable Muslim bases in northern Syria. It became the focal point of a new city established by a son of Saladin, al-Malik al-Zaher Ghazi.

The citadel was restored after the first Mongol invasion in

1260, then razed again in the second wave led by Timur in 1400. Later, as

the city expanded around the citadel, it lost its defensive role.

Elaine had a bath in the Turkish baths just outside the main gate. In the

city, we visited the souks, which were a real hassle, because you couldn’t

look at anything without instantly being jumped on by the stall-holders. But

that said we did buy some things, including Arab headresses (but not the Arafat

design).

Grinding groans, not grains: water wheels (noria), Hama

— Hama, one of the most picturesque cities in Syria, and memorable for its noria – huge, medieval-style waterwheels, which groan deeply as they turn on their great axles. One of our group thought she could compose music to the ever-changing frequency of the wheels: I suggested the title Symphony for Three Mopeds and a Distant Blue Whale. Those, at least, were the sounds conjured to my mind. But, though picturesque, in 1982 Hama was also the site of the worst massacre of the Assad regime. As you walk among the pepper trees, you can still see bullet and shell holes in some walls. Following an uprising by the Muslim Brotherhood, the Syrian army massacred anywhere from 5,000 to 25,000 people. Some 380 men were rounded up at random and shot. Whatever the human rights ‘take’, the Assad regime succeeded in silencing its critics and has since been one of the most stable in the Middle East. What price stability? And what price, longer term, sustainability?

— Damascus, which is where we started and ended

our tour, is a noisome, ugly city for the most part. Years of Soviet funding

created an unattractive eastern bloc aesthetic. But the city, which some argue

is the longest-settled city in the world (others argue for Jericho or Aleppo),

is full of treasures. The twelfth century Spanish Muslim traveller who said

that If Paradise be on earth, it is, without a doubt, Damascus, would be sorely

disappointed today. But this place has deep roots: it is mentioned in tablets

dating back to c2500 BC.

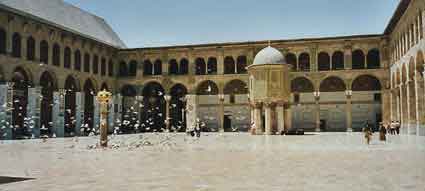

Among the places we loved were the Umayyad Mosque, surrounded by the much

nicer (than Aleppo’s) Hamidiye souk. Among other things, the Mosque has

survived invasions, Mongol sackings, earthquakes and a major fire in 1893.

Originally a Graeco-Roman temple to Jupiter (with one of the main gates now

embedded in one the Mosque’s walls), the site was later converted into

a Christian church, then taken over by the Muslims as a mosque. Inside are

two tombs said to contain the severed (now revered) heads of St John the Baptist

and of Hussein, son of Ali, the fourth Caliph after the death of Mohammed.

Nearby, too, are the tomb(s) of Saladin, one provided by Kaiser Wilhelm when

he was trying to win over the Muslim world, and of Baibars. This is a Sunni

mosque – and the welcome was distinctly warmer than at a Shi’ite

mosque, largely financed by Iran, that we also visited south of Damascus.

The tallest of the Umayyad Mosque’s minarets is the Tower of Jesus. According

to Muslim popular tradition, Jesus will descend from heaven via this tower

when the time comes to fight the Antichrist, prior to the Last Judgement

Sunni welcome at Umayyad Mosque, Damascus

What did you learn?

This was a study tour. And one of the key lessons, if it needed learning, was that even the greatest civilizations fail in the end. Build for the future and you can at least be confident that you will leave glorious ruins, or at least you could be until the advent of nuclear weapons. (Even before the A-bomb, many antiquities were shipped to European powers in the early part of the 20th century – and huge numbers were accidentally destroyed in the Allied bombing of Berlin.)

Under President Bashar al-Assad, whose posters and icons suggest a man with less charisma than either his late father or late elder brother, there may have been a softening of tone, but the secret services – the Mukhabarat – are still very much in control. When Freedom House published its 2001 survey, Syria appeared among the world’s 10 least free countries – alongside Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the Sudan. We saw little of the Mukhabarat, which was interesting, given that there are no less than six domestic secret service arms at work in Syria, much of their time spent on spying on each other. But we did see a lot of the military which, as in all other Arab countries, underpins the regime.

That said, most of the people we met were very friendly, partly no doubt because we were something of a rarity in terms of our willingness to visit the country. The children and young people were particularly welcoming, though you sometimes sensed this was something coached in schools. Having been nervous about going in the first place, we would love to go back some day.

But we also learned from Amin Maalouf’s Epilogue how powerfully the Crusades still resonate in the Arab world. If anything, this is even truer today. Take Saddam Hussein, for example. He is clearly proud of the fact that he was born in Tikrit, where Saladin lived nine centuries earlier. His latest palace features huge Saddam heads topped with copies of Saladin’s helmet. The more you look into the psychology of the Arab world, however, the more it seems that many Arab rulers are using the Crusades and the Palestinian/Israeli strife as an alibi for the harshness of their own regimes.

At the time, interestingly, the Crusades seemed to be a devastating defeat for the West, but Maalouf argues that they actually marked a turning point in the fortunes both of the West (surprisingly positive) and the Arab world (surprisingly negative).

Statue of Saladin at work, outside citadel, Damascus

The period saw the people of the Prophet lose control of their own destiny, with most of their leaders being foreigners, just as Saladin was a Kurd. "Dominated, oppressed, and derided, aliens in their own lands," Maalouf argues, "the Arabs were unable to continue to cultivate the cultural blossoms that had begun to flower in the seventh century." They were already living on past glories. And, unlike the Frankish invaders, they were bad at building institutions that resulted in a productive balance of power within a state. Whereas power frequently passed relatively smoothly between leaders in the Crusader kingdom, the death of an Arab leader was generally followed by a civil war.

Many Crusaders learned Arabic, but most Arabs saw any attempt at learning the Frankish languages as a betrayal. As a result, they learned little, while the Crusaders took home a rich booty of knowledge, much of it inherited indirectly via the Arabs from the Greeks, of such subjects as astronomy, mathematics, architecture, chemistry, fermentation and distillation, and so on. Maalouf sees the Crusades as one of the catalysts for the subsequent economic and cultural revolutions in Europe that culminated in the Renaissance.

In the Muslim world, meanwhile, such progress was increasingly viewed as alien. The Arab world largely turned in on itself. So we see periods of attempted modernism, like that of Atatürk in Turkey, alternating with periods of xenophobic traditionalism, as when Ayatollah Khomeini took over from the Shah in Iran.

Saladin and the victory over the Crusaders are still strong memories in the Arab world. The Crusades, says Maalouf, are deeply felt by Arabs, even today, "as an act of rape". As perceived enemies of the Arab world, any hostile action against the West "be it political, military, or based on oil – is considered no more than legitimate vengeance". Maalouf’s book was published in 1983, before the intifada (which began in 1987) and the events of September 11, 2001.

Small enterprise, puffing like The African Queen

Drive around Syria and you see many factories (e.g. refineries, phosphate works, a variety of grubby plants) producing pollution on a scale that would be totally unacceptable in the West. The mind-set of these countries was strikingly illustrated last December when Greenpeace confronted the Lebanese authorities with evidence of 143 outlets spewing raw sewage and toxic wastes into the Mediterranean. The lebanese environment minister’s response was to ask Greenpeace why they were "helping Israel".

With a booming population pressing hard, Syria’s political isolation – coupled with the collapse of its one-time Soviet sponsors – has left it one of the poorest countries in the region. So, with transparency and democracy seen as key preconditions for progress in sustainable development, what hope is there for Syria and the rest of the Arab world? It is tempting to say let’s wait and see, but my instinct is that all of this is going to be very much tougher for these countries than it will be for the West – and God knows it will be hard enough for us.

There are other concerns, too. Critics may be horrified by President Bush’s threats against Saddam Hussein’s regime, but I suspect that if some action is not taken we will have cause to regret that, too. Some of those who study Arab psychology warn that the governments of such countries as Iraq will not hesitate to use chemical and biological weapons against the West, once they have them. Meet ordinary Syrians and it is hard to imagine. And no doubt we should beware of thinking in terms of "Arab psychology". But the deep history of this region makes you wonder.

So is Islam to blame for all of this? Not really, says 85-year-old historian Bernard Lewis who has long studied Islam and advises the White House (Sarah Baxter, A word of warning from Arab history, Sunday Times, 5 May 2002). But he warns that "If the peoples of the Middle East continue on their present path, the suicide bomber may become a metaphor for the region and there will be no escape from a downward spiral of hate and spite, rage and self-pity, poverty and oppression, culminating sooner or later in yet another alien domination." Although Lewis argues in support of the notion of the "axis of evil", he does not see Islam as the main factor holding the Middle East back. Recall, for example, the way Islam fuelled the glories of Arab culture, science and technology in the centuries before the Crusades.

Other analysts are surprisingly optimistic. Francis Fukuyama, for example, believes that the terrorism we see today is merely a last-gasp, rearguard action "by a culture that will over time be modernized". Even within the Islamic world, he argues, "the hijackers do not represent a dominant trend, and over time they will have to confront modernization, and modernization will win."

My own perspective? The region’s problems stem from many factors, including colonization and the toxic mixing of corrupt, tyrannical regimes, which have created a power vacuum increasingly filled by the mosques, and resurgent fundamentalism. Whether in the Holy Land, Iran, Afghanistan or Iraq, western powers share much of the blame for creating the conditions that spawned the likes of the Taliban and Saddam. The oppressed populations, not least the Palestinians, will continue to act as incubators of hatred and terrorism. Like the followers of Simeon Stylites, the suicide bombers will find their echoes, no doubt in the West, too.

It’s not hard to see why many Arabs speak of western actions

in the region as reminiscent of the Wild West. But the Arab countries are

far from blameless. Past attempts give little hope of any short term improvement

in such areas as transparency, human rights and democracy, though these will

be pre-conditions for sustainable development. The purpose of this latest

trip report is to stress, once again, that we all need to use different lenses,

to open out our reality bubbles. That’s something I hope we can do continuously

through 2002 as we work out where SustainAbility can best invest its efforts

over the next 15 years.