Ignasi and Ernst

Ignasi and Ernst  Simon Longstaff’s hat

Simon Longstaff’s hat  Preparing for shoot

Preparing for shoot  Joris

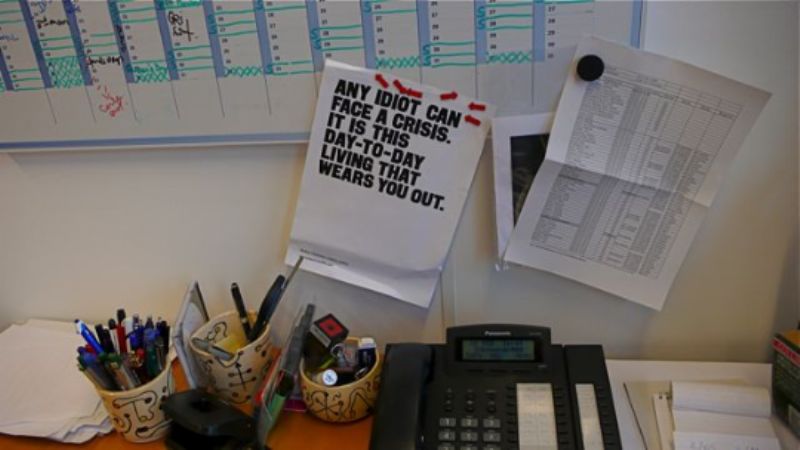

Joris  Nelmara’s office 1

Nelmara’s office 1  Nelmara’s office 2

Nelmara’s office 2

Am tapping away in the kitchen, with Monty Don on TV demonstrating a threshing machine which reminds me to some degree of thresher that was such a key feature of my younger days on a farm in Northern Ireland, and recalling the past two days in Amsterdam with the Board of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Have been struggling with flu for much of the time, despite the flu jab I had late last year. Luckily, several other people had the same problem, and, better still, the meeting ended early, so instead of flying back after 21.00, I got on a BMI flight around 15.35–though we had to stand in line to check in for over an hour, which with my damaged back had me swearing never to fly BMI again. Getting ready to fly to San Francisco tomorrow.