Good to see that GreenBiz has published an extract of my latest book today. They also plan to run my latest column next week.

Good to see that GreenBiz has published an extract of my latest book today. They also plan to run my latest column next week.

Loved this on Twitter this morning:

My guest column today on Atlas of the Future digs into the extraordinary work of Conservation X Labs, designed to help reverse extinction, where I recently joined the board.

Delighted to see the wonderful Rakesprogress magazine featuring this shot of a long-time family friend, Marina Ritschel (Instagram: @marinaritschel). The theme: ‘Spring Awakening’. The flowers were chosen and styled by our eldest daughter, Gaia Eros (Instagram: @stormandgraceflowers).

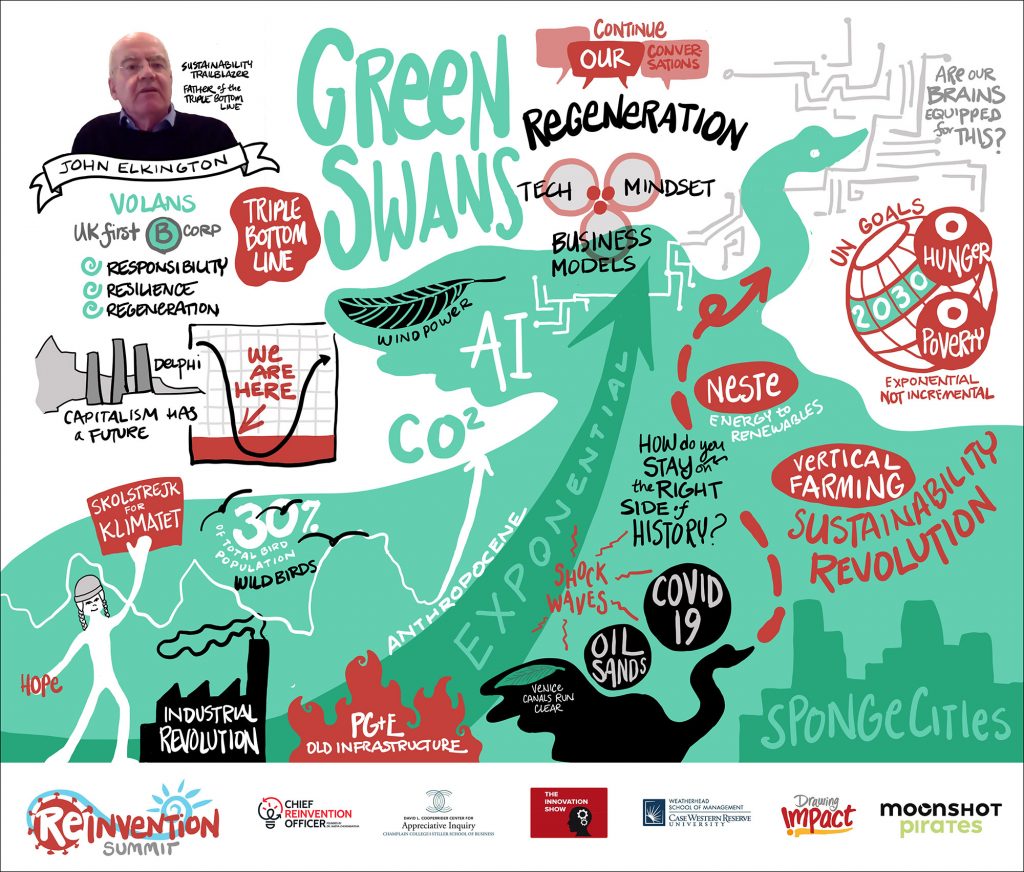

Delighted this morning to wake up to this visual capture of my virtual keynote yesterday evening for the Reinvention Summit, hosted by the extraordinary Nadya Zhexembayeva – who I first met when we both spoke at an Amfori conference outside Brussels. For more on her work, see here.

The illustration has been done by Angelique McAlpine, who you can track via the following:

LinkedIn: #scribeforward @Angelique McAlpine Twitter: @drawingimpact #scribeforward

Meanwhile, it’s amazing how technology has saved us as the COVID-19 outbreak and linked lockdown bites ever deeper.

Am doing a fair number of presentations via Zoom now – and finding it works very well. We have also ordered new equipment so that I can begin to do podcasts from home, where I am now “marooned”.

And what a pregnant word that is. Here’s the Merriam-Webster definition:

maroon verb marooned; marooning; maroons

transitive verb 1: to put ashore on a desolate island or coast and leave to one’s fate 2: to place or leave in isolation or without hope of ready escape

Of course it’s not like that at all. The newspapers come every morning, food is still somehow available, there is TV (where I have been relishing Netflix’s The Secret of the Nile series) and I am in constant connection with there wider world via the Internet and iPhone. Imagine is they went, too!

John Elkington is a world authority on corporate responsibility and sustainable development. He is currently Founding Partner and Executive Chairman of Volans, a future-focused business working at the intersection of the sustainability, entrepreneurship and innovation movements.