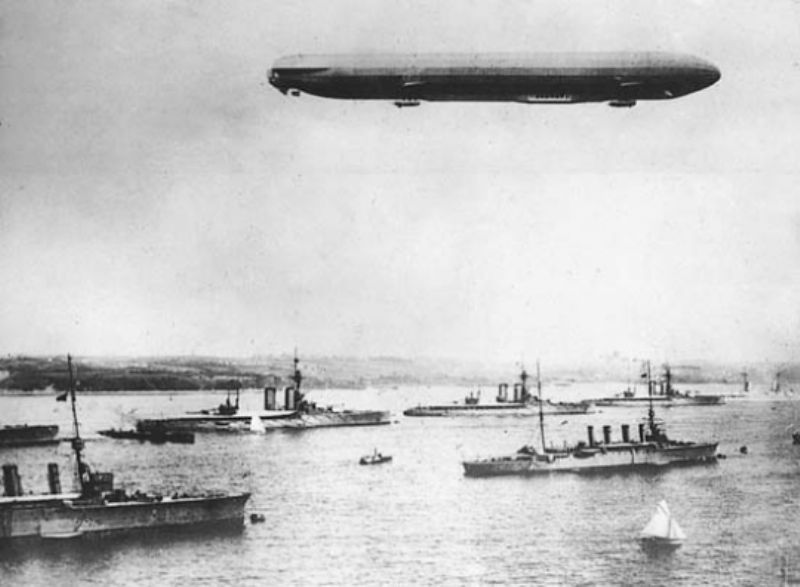

Zeppelin over fleet

Zeppelin over fleet

One of the things my father’s mother Isabel left us was a collection of diaries – and a couple of weeks back I was reading one from late 1916. At the time she was working as some sort of designer at the Admiralty, so it is written in a pale covered notebook, standard Admiralty issue she admits part way through.

Among many things that leapt out for me was her diary entry for Thursday, October 5. “Where can I begin?” she began – and the tale she told led me to an exploration of Britain’s ‘First Blitz’, a story told in the book I subsequently bought and read while flying to and from the US this week, Neil Hanson’s extraordinary First Blitz: The Never-Before-Told Story of the German Plan to Raze London to the Ground in 1918 (Doubleday, 2008).

The day began, once she was at work, with the sight of the French Republican Band playing in Horse Guards. Then she had lunch with her Aunt Jess and Vera (unknown) at the Lyceum, later seeing a concert featuring Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Then dinner at Pinoli’s, after which one of her stable of boyfriends – the one she dubbed ’17’, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy – took her home. “The Zepps were on the way,” she recalled, “and the trains were dark and unreliable, and we found everyone on the doorsteps looking for Zepps, so we went through to the garden to see them better.”

The airships seemed to work a strange aphrodisiac effect. “And then he made love to me – what could you expect? – most unreasonable – time – place – everything – but then when was love reasonable – and such love too.” The tale goes less well from there, but that’s another story. What struck me was her account of those bombed out of their homes – and her outrage at the looting that sometimes followed raids.

That led me to First Blitz. I knew that there had been Zeppelin raids over the southern parts of the country, particularly over London. I also knew that there had been raids by Gotha and Giant bombers, but I simply had no idea of the scale of those raids, nor of the physical, psychological and social impact they had. Substantial elements of the population teetered on the edge of panic as the raids built during ‘The Blitz of the Harvest Moon’.

Hanson’s book was an eye-opener in multiple dimensions, not least in terms of the lessons learned by England in terms of air defence, lessons that stood us in good stead when the second Blitz hit. Isabel, my favourite grandmother and a woman I always associate with London (where she lived in Pont Street and Lennox Gardens during the time when I knew her best, although I first remember seeing at her home in Dulverton), was in the city for the second time round during WWII, though I haven’t seen diaries from that era. One thing I do remember, though, is that once when she went down to stay on the south coast, at Hayling Island in 1940, she contrived to see my father, her only son Tim, shot down, but that’s a story I’ve told elsewhere.

In any event, the Zeppelin raids of October and November 1916 persuaded the Germans that the losses would be too great – and they then switched to winged aircraft, particularly the Gothas, whose exploits form the core of Hanson’s book. But one of the most interesting sections of the book deals with the use of fire in warfare, from the time when the Syrian Kallinicus came up with ‘Greek Fire’ in AD 660, a deadly weapon said to have saved Constantinople on many ocasions. It was squirted from siphons, as in modern flamethrowers. And the tale then goes on to the German plans to destroy as much of London as possible by triggering a successor to the Great Fire of 1666.

Those who feel Germany were complete innocents in the art of putting cities to the torch, that the WWII raids on cities like Hamburg and Dresden came literally out of the blue, should read the story of the ‘Fire Plan’ – and of just how hard the Germans tried to get the jump on Britain in the WWI fire department. Thank the heavens, or whomever, that by the time the Germans found an effective incendiary weapon, the Elektron, the war was in its closing stages. Indeed, the description of the last-minute interruption of the England Squadron’s first mass use of the Elektron is like something from a Buchan novel.

The Startoffizier is just about to wave the squadron’s aircraft into the night sky for the raid when suddenly, “through the darkness a car came racing … It was as black as night, its paintwork shining softly in the starlight, but the fluttering pennants it carried showed it bore an emissary of the High Command. It sped across the airfield, bumping and rattling over the rutted ground, driven flat out. Each Gotha, momentarily caught in the glare of its lights, loomed ghostly grey out of the darkness, then faded to a shadow as the car roared on.”

London and Paris were spared untold grief when Ludendorff cancelled the mission – and tens of thousands of Elektron bombs ended up being dumped into the River Scheldt. But incendiary bombs went from strength to strength in the following decades. Happily, just as in WWI, some WWII incendiaries failed to explode. We discovered that some years back when Elaine was ordered by a somewhat panicked policeman to get out of the house – without stopping for anything. It turned out that a stick of bombs had stalked down our road, in search of a nearby munitions plant, and that one had been sitting unexploded and undetected in a neighbour’s garden for some 60 years, about eight feet from where we still do the washing up.

And the truly extraordinary thing about Isabel’s diary? As I said to Gaia earlier today, it is as if she is talking to you, from 92 years ago, a modern voice, very self-aware, inquisitive, someone I often devoutly wish was still here to continue the conversations we had about so many things, but, sadly, never once about the aphrodisiac effects of danger and of Zeppelins.

Leave a Reply