Having been locked out of this site for several months, I thank Chris Wolf and Carlo Schifano for handing me back the keys.

With Gaia and family were in Canada, Hania and family in Tenerife, Christmas and the New Year were fairly quiet, though we saw various friends at different points. I found the long break liberating, plowing my way through several stacks of books, but also working on the new book I am developing with Charmian Love.

And, by way of a catch-up, here are some of the Substack articles I have posted in the meantime:

1. A kaleidoscopic survey of some of the things I was doing as 2025 wound down, including a trip to Florianópolis in Brazil and another session with AIRMIC and insurers and reinsurers.

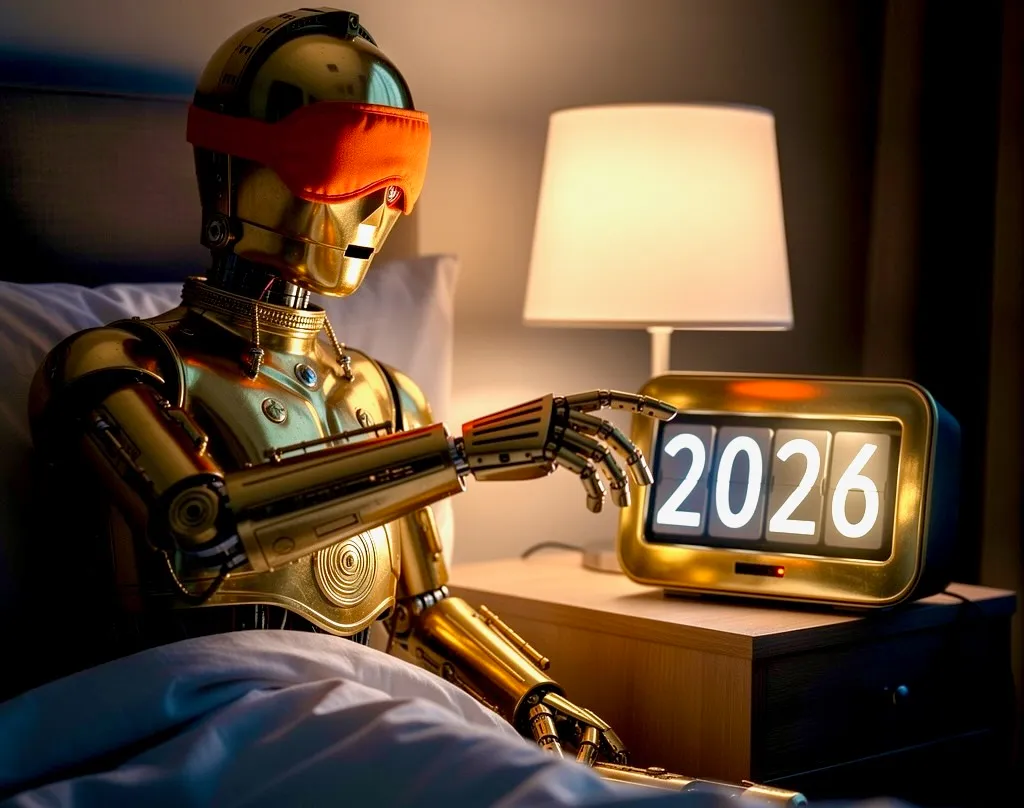

2. A well-received piece on where to channel our energy in 2026.

3. An even more warmly received post welcoming the New Year and discussing Trump’s entirely unintended gift to the sustainability world.

4. A piece inspired by the World Future Energy Summit in Abu Dhabi.

5. An exploration of some of the ways in which copper has underpinned our civilisations – and why it is now critical to the transition to greener economies.