With another train strike under way, we had to rent an car (turned out to be an Audi A4) to drive across to the Culham Centre for fusion energy, near Oxford. Bumped into Sir Martin Smith – not literally – as he got out of his red Tesla in the Culham car park. Among many other things, he is founder of the Smith School of Enterprise & Environment at Oxford University. (I followed up later – and Louise and then talked to Professor Cameron Hepburn, then Director of the School.)

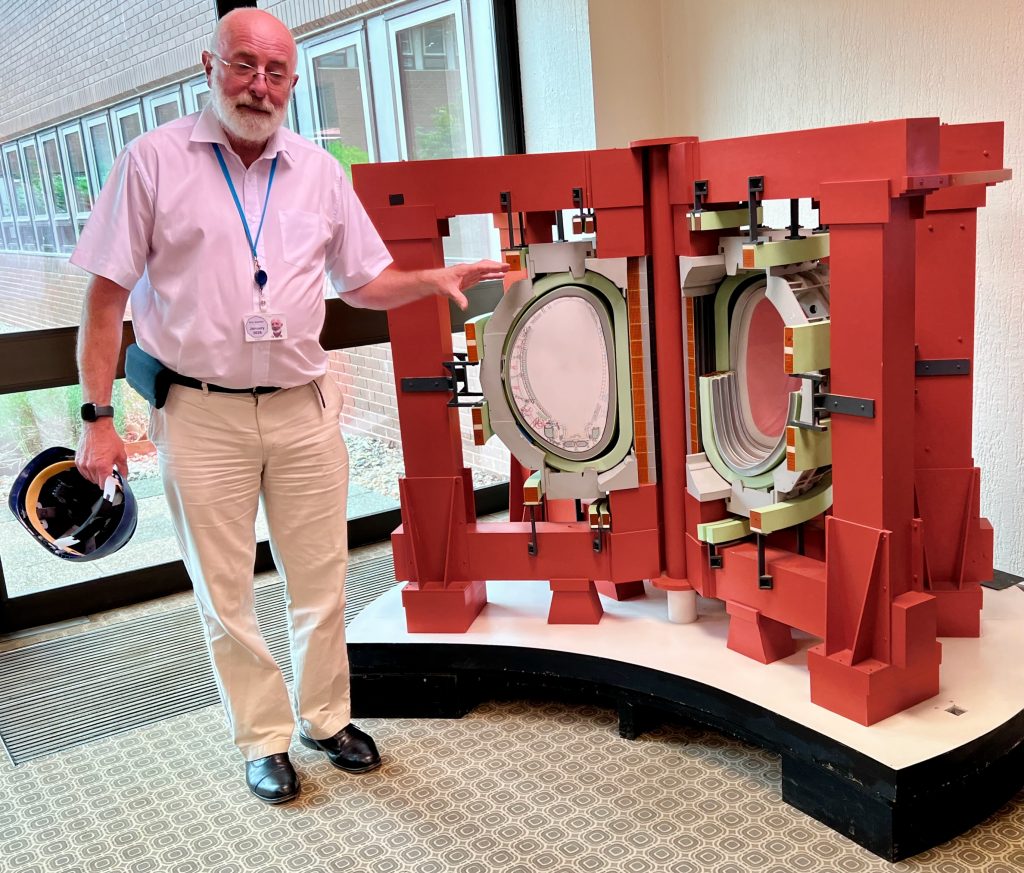

Fascinating briefing on nuclear fusion, followed by a tour, all organised by the Science Museum, where we have been patrons for some years. I wrote about fusion in my 1986 book Sun Traps, but things have changed enormously since then. For one thing, the private sector is now much more actively involved.

Next we drove across to Hill House to see Gray and Caroline – and were delighted to see how he has rewilded the gardens on either side of the house. Not sure our father, Tim, would have approved, but very much aligned with the zeitgeist.