Three mysteries solved since the Battle’s 50th anniversary—and some lessons learned.

Dedicated to Frederick George Berry (1914-1940)

The man who tried to kill my father is embraced by Göring

***

How glorious to sit beside a river, with no apparent beginning or ending, watching life stream by. Every day, I use Twitter in the same way, dipping in and out as the mood takes. But every so often a tweet, or a whole raft of them, jerks me back, like a fish snagged on a virtual hook.

That happened on August 8, when an early scan of the Twitterscape revealed a passing shoal of death notices, dating back exactly 75 years.

Someone I follow on Twitter, Pippa Ettore (@pettore), tweets regularly on Battle of Britain pilots—and this was a listing of some of those killed that same day in 1940. The names and the faces bobbed by … Sgt David Kirton, 21 … PO Johannes Oelofse, 23 … John Cruttenden, 20 … Ft Lt David Turner, 30 … FO Lord Richard Kay-Shuttleworth, 26 … PO Ernest Wakeham, 19 … PO Brian D’Arcy-Irvine, 22 … Ft Lt Noel Hall, 24 … PO Dennis Grice, 28 …

But who were these people? For clues, I turned to my 1999 edition of Men of the Battle of Britain, and the names came alive. In Dennis Grice’s case, it turns out that he stayed at the controls with his crew members, guiding their burning Blenheim clear of Ramsgate. All three died in the subsequent crash.

Turning to the book’s flyleaf, I was reminded that the dedication, to “No.1 Son,” came from my father, who flew with No. 1 Squadron in the Battle. And I also woke up to the fact that we were only a week or so away from the date when he, too, was shot down in flames. I thought I should update the story—and, in the process, say thank you to the man who saved my father’s life as his unconscious 19-year-old form dangled from his parachute and drifted the 10,000 feet down to the English Channel.

Fragmentary, Dr Watson

Like so many veterans, Tim (baptised John Francis Durham) Elkington tended to be fairly tight-lipped in the post-war era. Even when quizzed about the cannon-shell scars in his legs and about the oxidised black metal that would pop out of his back after a hot bath—shrapnel from his exploding fuel tank.

But constant badgering eventually began to tease open the covers on what has turned into something of a never-ending story. With its constant twists and turns, it reminds me of the rabbit hole in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Alice encounters the Caterpillar. ‘Who are you?’ he inquires, in a languid, sleepy voice. And she, en route to the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, replies that she really isn’t very sure, having changed size a number of times already that day. When he grumps that he is none the wiser[1], she says he will be when he has gone through metamorphosis and emerged as a butterfly[2].

Carroll had his finger on something important. In a rapidly changing world our sense of identity is complex, woven together out of threads plucked from the past, present and future. Some of us immerse ourselves in the past, some in the present, some in the still-to-come. Operating happily at either end of the spectrum, I have long devoured both History and Science Fiction, each shot through with rabbit holes or wormholes. Like Alice, you start off knowing where (and who) you are, but then, in a different reality, once-simple questions become harder to answer.

Happily, there are the moments when elements of a story somehow weave together into a striking new pattern. This has certainly been true of the still-emerging tale of what happened to Tim on 16 August 1940—and of the guardian angel who saved his life in the heat of battle.

*

Tim as back seat driver, aged 90 (Richard Paver, 2011)

Top Weaver blindsided

In an account I wrote for The Guardian in July 1990, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Britain, part of the story ran as follows:

***

A fighter pilot’s average life expectancy was 87 flying hours and a fair number died before they even had time to unpack their kit-bags. Nonetheless, on August 12, Tim claimed an Me. 109 [Messerschmitt Bf 109]. On the 15th, he also painted a mythical animal [see 3rd image below] on his Hurricane‘s cowling for good luck.

The next day he was “Top Weaver”, flying back and forth over the rest of the squadron to provide an early warning of enemy fighters, when they encountered 100 German aircraft. In the ensuing mêlée, he never saw the aircraft that riddled his plane with cannon shells – although, amazingly, his mother did. From nearby Hayling Island and quite unaware that her son was involved, she watched the lone Hurricane pursued by three Me. 109s. Tim’s fuel tank exploded, peppering him with shrapnel.

Perhaps not what most people would think of as good luck. Yet his luck did hold. Unconscious as he drifted seawards in his parachute, he would certainly have drowned. Then his flight leader, Flight Sergeant Berry, achieved the extraordinary feat of blowing him back over land with his aircraft’s slipstream. He was lucky in another way, too. On August 18, the RAF was put through the mincer on its “hardest day“, losing 136 planes.

[NOTE: In commenting on this blog, Tim commented that “riddled” was an inappropriate description of the impact of cannon fire.]

***

25 years on, key aspects of the story have become clearer. We now have answers to three questions that were still open back in 1990. First, ‘Who dunnit?’ Who opened fire on Tim’s top-weaving Hurricane? (We knew why.) Second, whatever happened to the main piece of evidence—the plane itself? And third, who was the man who saved Tim’s life as he fell 10,000 feet towards the sea?

So, first, who dunnit?

In a posting in this blog series on June 25, 2006, I reported new findings about the first question. One of the top-scoring Luftwaffe aces of the period, Major Helmut Wick, was the latest character to join the roiling cast.

A Swedish researcher, Christer Bergström, who has long studied WWII air warfare, had asked questions that spurred Tim into research that, in turn, suggested that the prevailing theory on who had shot him down (a former Luftwaffe pilot he had met at a West German embassy reception) was almost certainly wrong. One additional theory, which Tim has never credited, is that he was shot down by our own anti-aircraft guns near Portsmouth: he insists he saw no evidence of such guns in action at that time.

Bergström spurred Tim to check Luftwaffe and RAF records, and to contact several of the RAF squadrons in action in the area on that day. The upshot: it began to look very much as though the man responsible was Helmut Wick.

As it happens, I had come across Wick some years previously in Luftwaffe Fighter Aces: The Jagdflieger and their Combat Tactics and Techniques (Greenhill Books, 1996), by the delightfully named Mick Spick. Wick, I learned, had ‘understudied’ one of the ultimate Luftwaffe aces, Werner ‘Vati’ Mölders.

But why had he suddenly turned up on our radar screen after all these years? Well, take a look at Wick’s eighteenth ‘kill’. This happened on 16 August 1940—and in exactly the right place. For Wick, this wasn’t even half way through his eventual total of 56 kills, including an amazing 24 Spitfires, apparently making him the world’s top-scoring ace by the time he himself was killed a few months after his alleged attempt to saw off a critical part of what later would become my family tree.

Interestingly, if the Wick hypothesis is true, Tim is one of the kills recorded on the tailplane in Chris Banyai-Riepl’s extraordinary painting of Wick’s Bf109.

Helmut Wick’s Bf109, © Chris Banyai-Riepl

So what do we know about Wick himself? Well, he was one of Göring’s favourite pilots, as the photograph at the head of this blog shows. A pilot’s pilot. And Wick’s personal creed was crystal clear. “As long as I can shoot down the enemy, adding to the honour of the Richthofen Geschwader and the success of the Fatherland,” he said, “I am a happy man. I want to fight and die fighting, taking with me as many of the enemy as possible.”

This apparent death wish was fulfilled over the Channel on 28 November 1940. He was shot down by Flt Lt John Dundas, someone whose history I also already knew, because of his listing in Men of the Battle of Britain, underneath his brother, Hugh ‘Cocky’ Dundas.

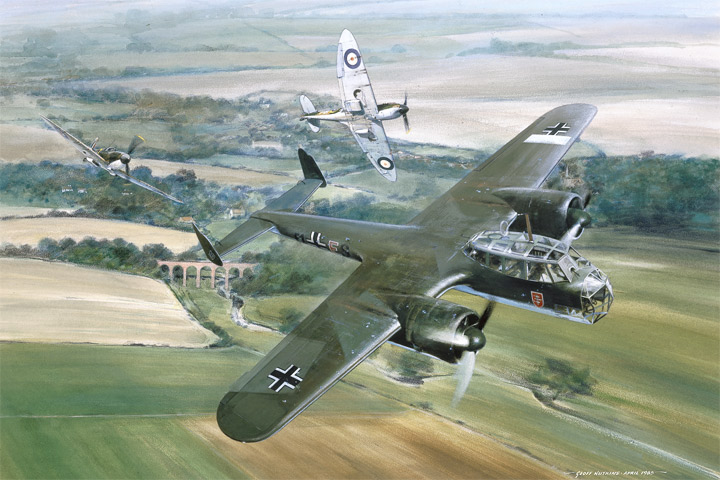

As a sidebar, the Dundas brothers were both aces—a fact dramatised by a painting (see below) by Geoff Nutkins of John Dundas and ‘Red’ Tobin in pursuit of a Dornier bomber. And when I was discussing all of this with my mother, Pat, she recalled meeting ‘Cocky’ Dundas years later—and being struck by the fact that he was as tall as Tim (like Roald Dahl, another WWII fighter pilot, something like 6’ 3” or even 6’ 4”). How did they fit into those cramped cockpits? [Tim says you could lower the seats.]

© Geoff Nutkins

Back to Wick: once he had been shot down, his No. 2, Hauptmann ‘Rudi’ Pflanz, is reported to have circled the area, trying to save Wick by calling in British air/sea rescue planes, radioing that a Spitfire was down. Nor was that a lie. Pflanz had shot down Dundas within minutes of the RAF pilot’s downing of Wick. Sadly, neither Dundas nor Wick were seen again

(A final, probably apocryphal, story I have heard is that Wick, given to wearing jackboots even when flying, was pulled under when they flooded.)

So, where did the evidence go?

When I wrote the 1990 piece for The Guardian, no-one had any idea about what had happened to Tim’s Hurricane when he finally managed to bale out. In a speech to No. 1 Squadron late in 2010, read out on his behalf by the pilot who had done a flypast for him the previous day, Tim recalled the post-attack sequence of events as follows:

***

In 1936, Olive Oyl gave Popeye ‘Eugene the Jeep’ – a mystical animal, capable of foretelling the future and materialising anywhere to work its magic. Just the thing for the nose art on my aircraft. I suppose you could say that it helped on the day it was applied – 15th August – when I achieved possible success in my first encounter with the Enemy. A smoking Me109 disappearing seawards through the clouds near Harwich.

Eugene the Jeep (possible origin of name of the Jeep)

But something slipped on 16th. With the help, a few years ago, of ‘Uncles’ in No. 1, 43 and 601 Squadrons, we are now fairly sure that I was the 18th victim of Helmut Wick when we were intercepting the raid on Tangmere. Quite an experienced chap, so I’m not too put out!

Leaving a burning aircraft is easy. You just throw yourself over the side. But first, make sure that you disconnect your Radio and Oxygen connections!

On the second attempt, I was out. Lovely sunny day, Portsmouth visible through the haze. No pain, just blood. But I was over the sea; had not thought to inflate my Mae West.

I remembered nothing more until there was a freckle-faced ambulance girl cutting my trousers off. A strange homecoming! Maybe Eugene was in fact still around, because Flight Sergeant Fred Berry, my Section Leader, came to my rescue and, somehow, with slipstream presumably, drifted me onto West Wittering. But only just! Without his aid I would have drowned.

As usual, my Mother was on her Hayling Island balcony with my Step-Father’s Naval glasses, watching it all happen. She was unsurprised when the phone rang from the Hospital 30 minutes later!

***

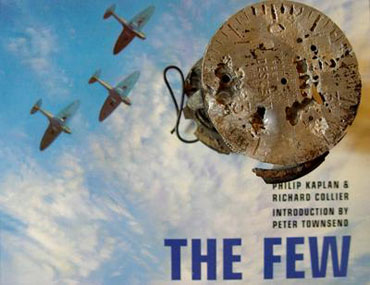

The Hurricane disappeared from history, among so much other wartime debris. But the fact that I now have its vertical speed indicator (see photograph below) hints at a further twist in the tale. The archaeologist Andy Saunders discovered the wreckage underground near West Wittering in 1975 [see last end note to this blog]. The big engines of such fighter planes tended to result in their burrowing (some say augering) deep into the earth, making them hard to find. But found it was.

*

The vertical speed indicator, atop a copy of ‘The Few’

So who saved the day?

Well, as my 1990 article noted, the simple answer was Fred Berry. But we knew almost nothing about him. When released from hospital two weeks later, and following sick leave, Tim tried to track Berry down to say thank you—only to find that Berry had been killed a couple of weeks after the incident, on September 1 1940. After the end of the war, Tim tried to locate any family through the RAF, but drew a blank.

But then there was yet another twist. As archaeological digs uncovered further parts of the Hurricane, I began to blog on the evolving story. As a direct result, I received the following email from John Hayes Fisher on February 6, 2004:

***

Dear John

I have come across your name on many occasions, probably initially through my degree (Environmental Studies) and in the New Scientist and almost certainly when I made a programme over 10 years ago on sustainability for BBC2’s Nature Series, when Michael Buerk was the presenter.

However the reason why I’m writing is completely unrelated. I am making a programme about the RAF’s No. 1 Squadron in the Battle of France and I was searching the web for references to armour plating being fitted to Hurricanes. I think it was with this search that I came across the article you had written in The Guardian about your father’s time with the Squadron and noticed reference to Flt Sgt Berry who was one of the pilots with No. 1 Squadron in France – and as you say was later killed in the Battle of Britain.

I believe that Berry was instrumental in saving your father’s life and I thought you might be interested in seeing a photo of Berry taken outside the town hall at Neuville, where the Squadron were billeted for the Autumn of ’39 and first part of 1940. I am also sending a copy of another photo I have found in the No. 1 Squadron scrapbook which we are borrowing for the programme. Needless to say, you will probably recognise the man third from the right.

Our programme is probably going out on BBC2 at 8pm on Saturday 21st February and is called Billy and the Fighter Boys. As I say, it’s about No. 1 Squadron’s time in the Battle of France and in it we follow aviation archaeologists as they discover the remains of Billy Drake’s Hurricane, which he bailed out of in May 1940, and excavate it while he is present.

Maybe your father might be interested in watching? Being in Billy’s company has left me with a deep sense of humility and admiration for the pilots of 1940, which I hope comes out in the programme.

Regards

John

***

Here is the photo John (Hayes Fisher) sent me of Fred Berry:

And here is the second photo, showing pilots of No. 1 Squadron standing in front of a Hurricane:

Pilots of No 1 Squadron, with Tim (my father) third from right

Once again, the story proved to have legs. As I recorded in a blog on June 6 2005, I received—when staying in the Edgewater Hotel where the Beatles had famously stayed back in the day—a momentous email from Belfast.

Berry’s granddaughter, Liese Brady, having seen the photo of Berry and Albonico (who appears to have been shot down and ended up a prisoner-of-war), had got in touch. It turned out that Berry’s wife (for whatever reason) had never mentioned his name after he was killed, so his daughter (Elisabeth Collins) and her own daughter had no idea of his bravery and exploits until they came across the accounts on this blog.

So, almost a lifetime after the event, the circle closed, with Tim finally able to correspond with Elisabeth and Liese. But then a computer crash wiped their email address from his hard disk—and I couldn’t find it either. Almost inevitably, fate interceded again. Some years later, Elisabeth and Liese came across to England, and Tim took them out to lunch at the Queen’s Hotel in Cheltenham. They were, he said, “immediate family”.

Elisabeth and Liese

Looking back

It is clear that the Battle of Britain has long since become one of those foundation stories around which Britain has built its post-WWII sense of identity. But it’s hard not to think of all those others, be they stokers on Atlantic convoys (Tim was a ‘Hurricat’ pilot on a CAM ship on an Arctic convoy, as mentioned here and here), the submariners enduring the terrors of depth-charging, or bomber crew flying endless missions over Germany (though at least they finally have their own powerful memorial in London), let alone those—including huge numbers of Indians—fighting in places like Burma.

Tessa (my youngest sister) and Tim at 70th anniversary event

Reunion photo taken by Tessa, Tim on far right

Over the White Cliffs, ditto

At one level, I am amazed that both my parents survived the Luftwaffe’s determined efforts to kill them. In one book on No. 1 Squadron, In All Things First, both my parents feature—Tim as a No 1 Squadron pilot, Pat as the target of a trio of Focke-Wulf 190 fighter-bombers in 1943, when she was serving as an ATS driver and driving battery commanders to a gun emplacement near Croydon.

It seems that these aircraft included at least one that went on to bomb the Sandhurst Road school in Catford, in what was called a Terrorangriff (“terror raid”), killing 32 children and 6 staff. If true, then the pilot who attacked the school was Hauptmann Heinz Schumann, born the same year as Fred Berry—and destined to die himself later in 1943.

Tim, middle of back row, at Clarence House, earlier in 2015

Though he doesn’t particularly welcome the spotlight, Tim has done more than his fair share of climbing in and out of WWII aircraft for sundry Battle of Britain memorial events. And much signing of commemorative prints, sometimes alongside former Luftwaffe foes.

But when surviving veterans like him are celebrated in places like Clarence House, and kindly hosted by people like HRH Prince Charles, we should imagine ourselves looking on through X-ray spectacles, revealing those others, long since gone, who contributed as much—and often more.

At their head, for me at least, would be the 534 (same say 537) airmen who were killed or mortally wounded during the Battle of Britain. And pride of place would go to Flight Sergeant Frederick George Berry—without whom I, my siblings (Gray, Caroline and Tessa) and Tim and Pat’s eight grandchildren would never have seen the light of day.

Flight of the Phoenix

Not exactly an Agatha Christie whodunnit, perhaps, but the story of how a number of small (if huge for us) mysteries have been solved over the past quarter-century. In that time, among other things, Tim has taken his place on the Battle of Britain Monument. Unbelievably, too, there are now plans afoot to rebuild his Hurricane, P3137 – though I suspect that this particular Phoenix won’t take flight.

Meanwhile, the bigger question of how we negotiate the twenty-first century without another world war, and without crashing the atmosphere and biosphere, remains wide open. It is a question we are dedicated to helping to tackle at Volans—whose name, no accident, comes from the Latin name for flying.

In that 1990 Guardian article, I argued that environmentalism would become “the most important political, social and economic movement globally by the year 2000.” Easy to predict, harder to achieve. Still, in the wake of Pope Francis’s recent Encyclical letter, Laudato Si’, two UN conferences later this year promise to help put the world’s foot firmly on the accelerator: the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in New York in September, and the COP21 climate conference in Paris in December.

In the midst of all this, the story of the pilots, aircrew and ground staff of those hard-fought days in 1940, truly their “Finest Hour,” provides strong clues as to how human ingenuity and determination can overcome seemingly impossible odds.

The pilots were only the sharp tip of a vast organizational iceberg against which Hitler’s plans capsized—just as today’s growing, global sustainability movement needs the efforts of millions of unsung heroes. Which makes Black Fish’s recent mention of the Royal Observer Corps as the inspiration for their Citizen Inspector Network even more poignant. Their goal is to radically reduce poaching and illegal overfishing.

On the look-out for volunteers (recruiting poster)

When we launched Volans in 2008, our first report was The Phoenix Economy. In the same way that the global economy my generation of Baby Boomers grew up with was a direct result of the travails of World War II, so the Millennials and their children will inhabit a world powerfully reshaped by the emerging One Planet Paradigm.

At times, this will be a war of the future against key elements of the past, with huge implications for leaders (addressed in our new boardroom dramatization, The Stretch Agenda) and, in the process, creating the biggest business opportunities of all time (signalled by our online market intelligence resource, The Breakthrough Forecast).

War brings out the best—and the worst—in us. The hard, bitter lessons must not be forgotten. But, as the Americans demonstrated with the post-WWII Marshall Plan, bitterness should not drive our strategy – even if climate-change-deniers and fossil fuel champions may tax our patience. The fact is that, this time, they are on the wrong side of History.

And one of our biggest challenges for the coming decades, as I noted in my contribution to Jørgen Randers provocative book 2052, will be to bend the military, the defence industries (often massively corrupt) and the intelligence agencies (often massively distracted) to the new task of providing leaders with ‘tomorrow’s intelligence’—and the evolving economy with some of the technologies, logistics and muscle power around which a truly sustainable economy can be built.

As I finished this blog, I began to read the manuscript of a forthcoming book, Can the World Be Wrong? The sub-title: Where Global Public Opinion Says We’re Headed. Having been invited to provide the book’s foreword, written by a friend, Doug Miller of GlobeScan, I read it cover to cover. Right at the end, on page 249, I saw that Doug quotes that extraordinary Winston Churchill line:

***

“It’s not enough that we do our best; sometimes we have to do what’s required.”

***

And that struck me as a particularly fitting place to end—or, perhaps, begin.

John Elkington

16 August 2015: With thanks to family members, to Pippa Ettore and to several Volans colleagues for their comments on earlier drafts.

[1] The title of a memoir by my mother’s youngest brother, Paul Adamson.

[2] Tim’s parachute descent towards West Wittering qualified him as a member of the informal Caterpillar Club.

* Extract from Liese Brady‘s response on 16 August: “[Fred, her grandfather] was married for only 6 weeks before he was killed (Mum being a honeymoon baby!) so Mum never met him. My grandmother never really spoke of him. She never remarried and wore her wedding ring right to the day she died.”

** Extract from Andy Saunders‘ response to a draft on 15 August: “[The first dig to recover parts of the Hurricane, in 1975] was organised by me, yes. Officially it was an operation by what was (then) the Wealden Aviation Archaeological Group (WAAG), which no longer exists. I have a photo of your control column which, sadly, was stolen from the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum c.1984.”

I really enjoyed reading your blog and the story from the war with all the historical facts and a reference to classical litterature and Alice in wonderland! The link to today´s movements and SDGs was also very inspiring. I believe that is the only way for reaching the goals – that we all do as much as we can each day to save the planet. That will eventually, and very soon I hope, create a happy, sustaiable, and liveable planet earth. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you so much, wonderful to read, sad in some places, uplifting in others, inspiring that research and perseverance can reveal so much that could be knit history together.

What an extraordinary chain of events. I was prompted to read by hearing the unusual name of Time Elkington on the news. I knew of one in a framing context, who (I think) had contacted me [not sure if it was by phone or letter, maybe both] after I wrote a series of articles on the subject for “The Artist” magazine in the 1980s, or possibly when I advertised a mount-cutting service in “Artists’ Newsletter”. At some point, I must have mentioned that I’d worked out a theory for a mathematical calculation of use to framers, and he wanted to know more about it. Somewhere in the correspondence, the pairing of “Durham and Caroline Elkington” must have arisen (most likely on a letterhead or some other document). This, completely forgotten for 25 years, was triggered when I heard the name Durham in connection with Tim (though I see it occurs in several other Elkington names, all surely from your family). I seem to recall that Tim was a pretty busy correspondent in the Framing publications I read. Of course I had no idea of all the RAF background. I was trying to work out if a 98-year old would still have been in business early in my career; clearly so! I’m glad I read right to the very bottom of this piece to twig who Caroline is.

My condolences to you all.

I enjoyed many Emails and replies from Tim Elkington between 2010 and when he died. He loved me paying tribute to Fred Berry over many years in the Battle of Britain Historical Society site, Pippa Ettores site or my own Battle of Britain Site, on Facebook andTwitter. I was honoured to be a friend and reunited him with a spar from under his Hurricane seat, bought on the internet. He recognised it as being close to his feet, on the Hurricane shot down by Helmut Wick. Excellent article. One correction. When killed, Wick had just equalled Adolph Galland’s victories that date of 28 November . Galland claimed 57 as top ace for 1940. Wick was killed by Dundas after being hit by another pilot and came second with 56 victories and Werner Molders claimed 55 by December 1940. It was an honour knowing your father.I have written many stories if him also, to his embarrassment, and he woke never let me call him a hero – which he was, of course. Paul Davies Aviation Historian, Battle of Britain Site.