Not exactly sure why, but I have a strong sense of a tide (or tides) turning at the moment. A more or less constant sense of imminence, of emergence. Whether I am working with clients, developing speeches or planning the launch of my latest book, Green Swans, in April.

All of which puts me in mind of a strange (but best-selling) book I read on a flight in the USA back in the 1990s, The Celestine Prophecy. A story of ancient wisdom from Peru – a country that sat on the Volans sofa on Thursday morning, in the shape of Martin Morales, the Peruvian restaurateur and chef. Martin was introduced to me by Jessica Kruger of LUXTRA.

A fascinating conversation, at least for me, including his development of the Andina restaurants and his role in music production across the decades, among other things with Tiger’s Milk Records, and his discovery of artists like KT Tunstall – who I first heard at the Skoll World Forum back in 2009.

In any event, a late theme of the Celestine book was that as the world heads towards a major inflection point the frequency of coincidences goes off the scale. That stuck in my mind – and that’s very much my experience at the moment, on some sort of speed.

Once the brain is in this mode, everything potentially becomes significant, numinous. Particularly the natural world. As on Tuesday, when I heard a woodpecker hammering away energetically as I walked across Barnes Common to the station early in the morning, for a meeting at the Conduit Club with Diana Fox Carney – and then again that evening, after a wonderful call with the Harvard Business Review, the first brown owl I have heard in many years, hooting repeatedly.

The coffee with Diana – with whom I serve on the WWF UK Council of Ambassadors – unexpectedly led to an invitation to attend a breakfast meeting hosted by Pi Capital. This was held at the extraordinary Langan Brasserie, dating back to 1976.

There, Diana introduced the speaker, Professor Myles Allen of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute. I was blown away by the crystal clarity of his explanation of the atmospheric chemistry and physics of climate change.

Afterwards, I tubed across to Covent Garden, once again deeply thankful for my Bose headphones. Tinnitus and hyperacusis aren’t much fun on old subways.

Then strolled down towards Waterloo Bridge and Somerset House. The morning light was exquisite, which all added to that sense of things being internally illuminated – and somehow in transition.

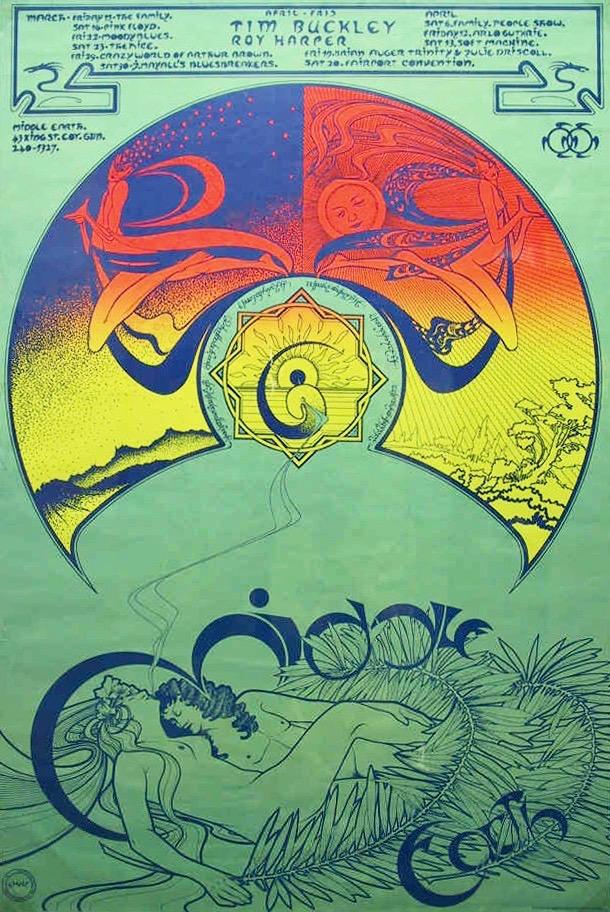

As I walked past the Apple Store, a modern day temple (see mention of The Enchantments of Mammon below), I recalled how we used to go to a very different “temple”, Middle Earth, in the late 1960s – the underground (in multiple senses) club at 43 King Street.

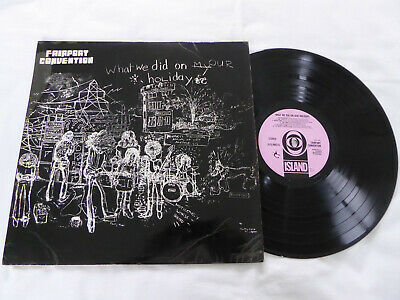

There we would listen to bands like Pink Floyd, Tyrannosaurus Rex, Fairport Convention and The Byrds, during their Gram Parsons days. Sometimes with the late, great John Peel DJ’ing. And the most spectacular light shows.

Then, last night, Elaine and I watched the 2017 documentary on Fairport which I had recorded a few days back. Recalled the times we saw them at Essex University – including on the evening that was later enshrined on the cover for their album What We Did On Our Holidays. My ears are still ringing from the concert, though that’s maybe the tinnitus.

As I walked down memory lane, en route to Somerset House, I also recalled some of the other connections we have had with Covent Garden over the years.

These included working with Mike Franks (who would later set up Regeneration, then The Regeneration Trust) while I was doing my UCL M.Phil. and he was a GLC planner during the redevelopment of the central market area; the office I first worked in with John Roberts and TEST in King Street, a firm I joined in 1974; then came TEST’s move to Floral Street (in a building long since replaced by a modern development); and then Elaine working with Wildwood House on the floor below, the publishing company set up by Olly Caldecott and Dieter Pevsner.

The constant interweaving of lives. Olly’s wife Moyra recalled many things in this piece, but among them she described her angina being cured by a spiritualist healer, Dennis Barrett, a former merchant seaman. Again, the year was 1976.

As it happens, Moyra recommended Dennis for my sinusitis, contracted back in 1973, when I worked on the BRAD alternative technology farm set up by Robin Clarke, former editor of the Science Journal.

Thanks to Moyra, Dennis came up from Bristol by train, again in 1976. He would accept no fee (though we gently insisted on paying a donation to his church). As for the treatment, he laid his hands on me while I sat on a wooden chair (one of a pair that came with the house and are now in our daughter Hania’s home). All of this in the midst of the rubble of the building in Barnes that has been our home ever since. The effect was as though I had been given a general anaesthetic.

In my memory, Dennis was a large, slightly looming man – and yet radiated a profound sense of peace, gentility and goodwill. He told me that it would take three months for the treatment to have an effect. Almost three months later to the day, I woke up to have Elaine point out that a condition which had dogged me for years (and for which our GP was recommending literally nose-breaking surgery) was gone. Thank you, Dennis.

Then, while researching this post, I found references to a book on him that I had never heard of – The Healing Spirit: Story of Dennis Barrett – published back in 1990/1992. Now ordered.

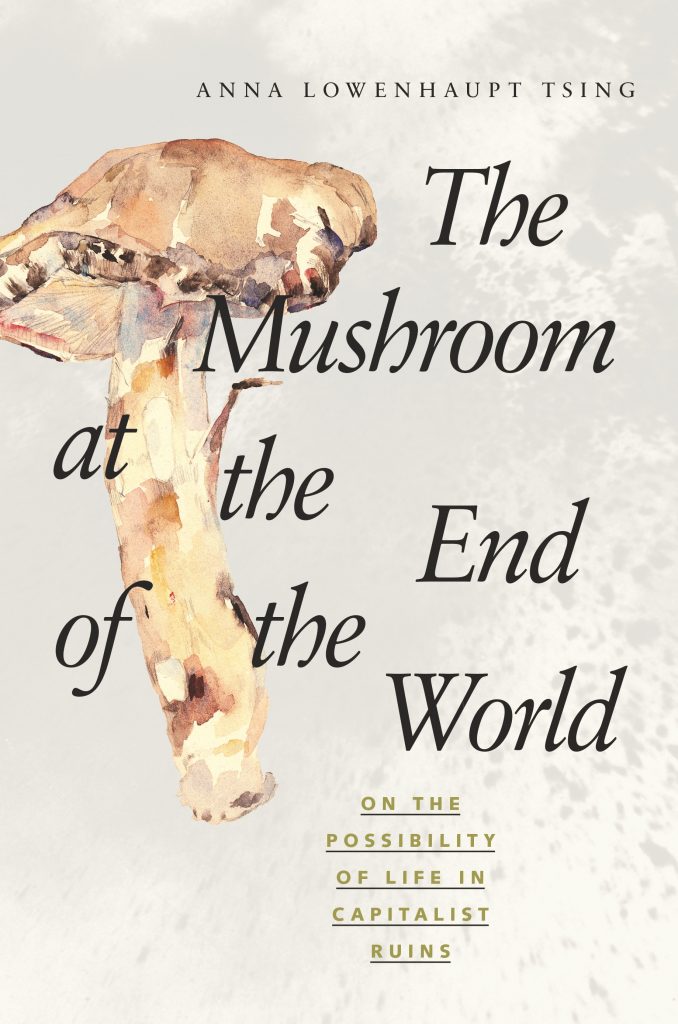

Further connections erupted on Wednesday this week when Elaine, Gaia, Hania and I went to see the Mushrooms exhibition at Somerset House. Apart from all the hallucinogenic fare, taking me back to Middle Earth times, there on display was a copy of The Mushroom At The End Of The World, a book I bought some years back, but have yet to read properly.

By Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, the book covers the following territory, according to publishers Princeton University Press:

Matsutake is the most valuable mushroom in the world—and a weed that grows in human-disturbed forests across the northern hemisphere. Through its ability to nurture trees, matsutake helps forests to grow in daunting places. It is also an edible delicacy in Japan, where it sometimes commands astronomical prices. In all its contradictions, matsutake offers insights into areas far beyond just mushrooms and addresses a crucial question: what manages to live in the ruins we have made?

A tale of diversity within our damaged landscapes, The Mushroom at the End of the World follows one of the strangest commodity chains of our times to explore the unexpected corners of capitalism. Here, we witness the varied and peculiar worlds of matsutake commerce: the worlds of Japanese gourmets, capitalist traders, Hmong jungle fighters, industrial forests, Yi Chinese goat herders, Finnish nature guides, and more. These companions also lead us into fungal ecologies and forest histories to better understand the promise of cohabitation in a time of massive human destruction.

The book has now rocketed back up my reading list, once I have finished the three books I am currently reading in parallel: William Gibson’s Agency, Jeff Vandermeer’s Dead Astronauts, and Eugene McCarraher’s stunning book, The Enchantments of Mammon.

Dead Astronauts, in particular, is hallucinogenic, as when a character breaks down into 50 green salamanders, each with its own eyes and beating heart.

In similar vein, on Wednesday The Times carried an obituary of Ricard Alpert, aka Baba Ram Das, a colleague of the fabled – or perhaps I should say notorious – Timothy O’Leary. The weirder end of the Sixties, but having once taken LSD (back in 1969; it lasted intermittently for four years), not an inconsequential influence on my life and times.

On Thursday I had a wonderful lunch with Samer Salty, founder and managing partner at Zouk Capital, on and – at his kind invitation – it was at Zuma, which specialises in modern Japanese cuisine. Didn’t see matsutake on the menu, but who knows.

All of which may seem a long way from today’s sustainable business and investment agenda, but all of which was part of the mulch in which these agendas took root. Of which fact I have been reminded as I have tried to work out how best we can help acknowledge the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on 22 April.

I mentioned this milestone event in a question to the panel at the Science Museum’s event on Wednesday celebrating the first year of its STEM Circle corporate membership programme. The evening focused on the prospects for “Clean Growth” – a topic at the heart of the UK’s Industrial Strategy, laying out an ambitious blueprint for Britain’s low carbon future.

In a week when downside news showed temperatures hitting a record in Antarctica, upside news had Elon Musk’s Tesla built a stunning lead over traditional auto-makers as the world appeared to pass some sort of tipping point on the transition to electric vehicles.

The 2020s, it is increasingly evident, could see a range of wild visions becoming reality – be they Black Swans, largely driven by negative exponentials, or Green Swans, largely driven by positive exponentials. But more of that anon. Meanwhile, that was part of the week that was.

Leave a Reply